The Italian art critic, Phillipe Daverio, puts it nicely: ‘We’re all victims of the architect … You can avoid paintings, you can avoid music, you can even avoid history … good luck getting away from architecture. ’Here in Maleny we’re a case in point. We inhabit an architectural vacuum, a no-place of thrown-together buildings that wear a bleak and abandoned look even before they’re finished. With some very few exceptions it’s actually getting worse. You think I’m being too harsh? Consider our new Police Station. Constructed out of ex-1950’s toilet-block brick it crouches beside Macadamia Drive, huddled amongst its cramped loading docks, hiding its face from the world from shame at its ugliness, doing its best to reference nothing so much as the old Masonic Hall over on Tamarind Street, itself a spectacular example of poor design and worse realisation. What’s important to note about this is that the Police Station is the first public building to arrive in Maleny for a long time – or no, not quite, because there’s another, over on the Precinct – something that’s supposed to be a museum in the making but at this stage is no more than the cheapest of tin sheds with a roll-a-door frontage and no public access to the toilets (which, I might be mistaken, but to deliver was one of its briefs). Does this matter? Yes, and yes again. Apart from the problems which arise for people who have to live and work in poorly designed buildings there is the effect they have on the community around them. Public architecture provides the stimulus for private endeavour. If we can’t, collectively, put up structures that make us proud, then why should any private business or home owner bother to even think about doing the same? The Beersheba Light Horse Museum on the Precinct is the first public building to be erected on a large piece of land adjacent to town, a piece of land which could, if properly envisaged, change the way our whole community develops. On the basis of this first building it looks like we are in for a carbon copy of the showgrounds with its motley collection of shacks and tumble down sheds resembling nothing so much as a blown apart shanty town. And I hear the arguments being raised even as I dare to suggest there’s something wrong with this: there’s no money. To which I cry rubbish. Our society today is richer than it has ever been in its history. Far, far richer than it was in the nineteenth or even the twentieth century when it was seen as important to construct schools and town halls and libraries, even museums, that reflected the importance of a civic world. We are not helped by having a Council that is pedantic about the smallest things but lacks any vision of what our community might want to look like and is too busy promoting development to ask. It’s time we demanded better. Otherwise we’ll be condemned to live amongst buildings like the brutal box that’s just been constructed behind the old butter factory.

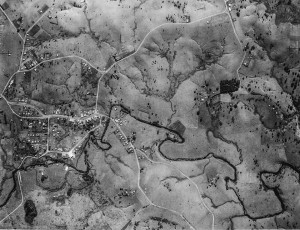

This morning, for the first time ever while listening to the morning chorus, I did not hear a kookaburra. Normally they announce the day. I hear their cry from somewhere off in the bush so distant as to almost only be imagined, but approaching, rising up around us, calling in the light. It is only when they are done their caterwauling that the whipbirds, the lewin’s honeyeaters, the thornbills and the pigeons start their conversations. Perhaps the kookaburras were away this morning. On holiday in France or Turkey. Taken a cheap flight to Tasmania or New Zealand for a break. I hope it is so. I read, recently, that the kookaburra is in decline across eastern Australia. To be honest I didn’t read the whole article because I didn’t want to know. Habitat loss or some such thing which, I assumed, didn’t apply to me here, where I live next to the rainforest, although that wasn’t the reason I didn’t pursue the subject, it was more that I couldn’t bear the thought of a world without their call.Habitat loss was the reason that I gave over several years to creating a corridor of trees that follows the main watercourse up here on the Range where I live. I’d seen the aerial photographs of what the place had looked like from the thirties through to the seventies, when the land-clearing was at its peak, when there was hardly a stick left standing across the whole rolling expanse. At that time there were, no doubt, still forests further afield, but here, in the prime dairy country, the trees had gone; they’d been cut and milled for timber or simply burned. The stumps dug out. It seemed to me that now, when those wider forests too were cut, as the existence of a landscape in which other species than humans could survive was becoming more threatened, that it would be a good idea to try to create links between the remaining habitats, even to create new ones where old ones had been.One of the extraordinary things to me about the natural world is the way the things that live in it manage to do so. That this tree, this shrub, this grass, this lizard, bird, marsupial mouse, somehow all manage to eke out a life without the benefit of a supermarket down the road, or a social services system, without, indeed, any help from anyone else. They each and every one every day manage to scrape out a living. I understand, of course, that it is the vast complexity, the tens of thousands of beings from microbes up to mammals all living cheek by jowl, in conjunction with the weather (rain, sunshine, wind) which is, in fact, the social services network that provides the means for them to live. But it is not, it seems to me, unreasonable to notice that I could not manage what they do myself. I do not think that it is romantic of me to think like this. I think it is practical, pragmatic, essential.I want the kookaburras and their support network to continue to survive, not because they give me anything (other than the pleasure of their early morning or late evening noise) but because I think they have an intrinsic right to do so without members of my species depriving them of that ability in order to be able to have one more piece of disposable crap they didn’t even really want in the first place. I’m not sure that such a desire is really so unusual, or so primitive an ideal.What struck me as strange as I went about the business of creating that small wildlife corridor – two kilometres long by forty metres wide – accessing funding, then rights to the land, partners and co-workers to undertake the project, was the fierceness of the opposition of my fellow men and women. The extraordinary lengths they went to in order to try and stop me. The land was needed, they said, for sport, or golf, or horses. They even came up with pseudo science intended to demonstrate that the creek banks would be better off without trees, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Their cause, their aim – as intelligent, affluent westerners who must be as aware of habitat loss as I am (residents in the same wider ecosystem) – was a mystery I have not solved yet, nor resolved within myself. In the end it all became too hard for me, the politics of it, not the planting and weeding, the fence-building and nurturing. I gave it over to others who, thankfully, kept the program going and eventually completed it.Perhaps, though, it is time to shake off my reluctance and once again consider taking up the baton. The original need remains: today, in the morning chorus of birds, I did not hear a kookaburra. I do so much hope it was an aberration.

Perhaps the kookaburras were away this morning. On holiday in France or Turkey. Taken a cheap flight to Tasmania or New Zealand for a break. I hope it is so. I read, recently, that the kookaburra is in decline across eastern Australia. To be honest I didn’t read the whole article because I didn’t want to know. Habitat loss or some such thing which, I assumed, didn’t apply to me here, where I live next to the rainforest, although that wasn’t the reason I didn’t pursue the subject, it was more that I couldn’t bear the thought of a world without their call.Habitat loss was the reason that I gave over several years to creating a corridor of trees that follows the main watercourse up here on the Range where I live. I’d seen the aerial photographs of what the place had looked like from the thirties through to the seventies, when the land-clearing was at its peak, when there was hardly a stick left standing across the whole rolling expanse. At that time there were, no doubt, still forests further afield, but here, in the prime dairy country, the trees had gone; they’d been cut and milled for timber or simply burned. The stumps dug out. It seemed to me that now, when those wider forests too were cut, as the existence of a landscape in which other species than humans could survive was becoming more threatened, that it would be a good idea to try to create links between the remaining habitats, even to create new ones where old ones had been.One of the extraordinary things to me about the natural world is the way the things that live in it manage to do so. That this tree, this shrub, this grass, this lizard, bird, marsupial mouse, somehow all manage to eke out a life without the benefit of a supermarket down the road, or a social services system, without, indeed, any help from anyone else. They each and every one every day manage to scrape out a living. I understand, of course, that it is the vast complexity, the tens of thousands of beings from microbes up to mammals all living cheek by jowl, in conjunction with the weather (rain, sunshine, wind) which is, in fact, the social services network that provides the means for them to live. But it is not, it seems to me, unreasonable to notice that I could not manage what they do myself. I do not think that it is romantic of me to think like this. I think it is practical, pragmatic, essential.I want the kookaburras and their support network to continue to survive, not because they give me anything (other than the pleasure of their early morning or late evening noise) but because I think they have an intrinsic right to do so without members of my species depriving them of that ability in order to be able to have one more piece of disposable crap they didn’t even really want in the first place. I’m not sure that such a desire is really so unusual, or so primitive an ideal.What struck me as strange as I went about the business of creating that small wildlife corridor – two kilometres long by forty metres wide – accessing funding, then rights to the land, partners and co-workers to undertake the project, was the fierceness of the opposition of my fellow men and women. The extraordinary lengths they went to in order to try and stop me. The land was needed, they said, for sport, or golf, or horses. They even came up with pseudo science intended to demonstrate that the creek banks would be better off without trees, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Their cause, their aim – as intelligent, affluent westerners who must be as aware of habitat loss as I am (residents in the same wider ecosystem) – was a mystery I have not solved yet, nor resolved within myself. In the end it all became too hard for me, the politics of it, not the planting and weeding, the fence-building and nurturing. I gave it over to others who, thankfully, kept the program going and eventually completed it.Perhaps, though, it is time to shake off my reluctance and once again consider taking up the baton. The original need remains: today, in the morning chorus of birds, I did not hear a kookaburra. I do so much hope it was an aberration.

Late last year Chris and I started a small business renting our studio on the property where we live as self-contained accommodation. We did a major renovation on the place, laying a new floor, installing air-conditioning, painting it outside and in, completely refurnishing it, refining the kitchen. The idea was to make it as beautiful as possible, to provide guests with an experience they could treasure, to make a place worthy of its location.We’ve been letting it now for seven months and the response from guests has been extremely encouraging. Check out the website for more images and comments (or for availability).

In the most recent issue of Rolling Stone Magazine there is a long and profoundly fascinating article by Al Gore on the climate situation entitled The Turning Point, New Hope for the Climate. It is a polemic which is full of both hope and despair, with the former, well it would be wrong to say triumphing, but at least winning out over the latter.He starts by describing the incredible advances in renewable technology, in particular solar, and what that means, how it is manifesting in different parts of the world, going on to list some of the forces ranged against its deployment. For the centre part of the piece he inevitably outlines the damage that is being done and will be done by changing weather patterns, but towards the end he takes time to point out the failure of 'democratic capitalism' to address the problem, before finally coming back to a call to action, bolstered by hope. As he says in the last paragraph, quoting Martin Luther King, 'The arc of the moral universe is long but it tilts towards justice.'This piece ties in well with another by the inimitable Bill McKibben in the New York Review of Books on the book Walden Warming: Climate Change Comes to Thoreau's Woods by Richard B Primack.It seems that Henry David Thoreau was not only the author of one 'of the greatest books any American has ever produced', he was also a formidable naturalist, spending a minimum of four hours a day walking in and around Concord, taking notes. Those painstaking observations of the timing of such natural events as the budding of flowers in spring are being used to measure the behaviour of the same plants 160 years later. The results are, generally, not good. As McKibben points out, the Sierra Club has recently ended its 120 year prohibition against engaging in illegal protest, explaining that the ongoing climate emergency required more intense engagement than they'd had so far.What these articles seem to me to suggest, and it might be that I'm just an optimist, is that, at least in other countries, some sort of tipping point has been reached in the so-called debate about Climate Change; that the effects we have already seen are dramatic enough to at last begin to exercise the minds of politicians. That Australia, with a government which is no more than the political wing of the Murdoch Press and the fossil-fuel industry, is going the other way, is a matter of deep shame and concern.

Over the last year this blog has slipped into somnolence, pushed aside by family (two grandchildren, a daughter's wedding), other sorts of writing (a new novel in first draft), politics and conservation (two big tree plants and much lobbying), outspoken (Bill Gammage in July) and now ... building.In an attempt to rationalise this house we're adding an extension and replacing the deck. If I'm not too tired at night I will try to make this build, its design, its philosophical and physical implications, the subject of the blog. As well as the occasional photo.

Writing today is interrupted by a family of spangled drongos in the bunya pine next to the studio. The parents have raised three young in a nest about a hundred metres away but this is the first time I’ve seen the babies out and about. They perch on the horizontal branches waiting to be fed. Every time one of the parents comes in sight all three shake their wings and call out in their infectious chatter, ‘Pick me, pick me.’ The tireless red-eyed adults with their wonderful swooping fish-tails (the babies have yet to develop either of these) regurgitate whatever insect they’ve caught into the waiting mouths.These birds are the most delightful of our summer residents. They appear around the beginning of October, having made the extraordinary journey from Papua New Guinea, and stay until late March when they return north. Their call is unique, a sort of stone rattling laugh, occasionally tinged with a melodious metallic quality reminiscent of something Telstra might produce deep in a copper wire. Today, however, the mother is producing a single repetitive high note that I’ve never attributed to her before, telling her children to sit still and behave and that the man on the studio veranda with the camera is okay, even if he is a man.

Every time one of the parents comes in sight all three shake their wings and call out in their infectious chatter, ‘Pick me, pick me.’ The tireless red-eyed adults with their wonderful swooping fish-tails (the babies have yet to develop either of these) regurgitate whatever insect they’ve caught into the waiting mouths.These birds are the most delightful of our summer residents. They appear around the beginning of October, having made the extraordinary journey from Papua New Guinea, and stay until late March when they return north. Their call is unique, a sort of stone rattling laugh, occasionally tinged with a melodious metallic quality reminiscent of something Telstra might produce deep in a copper wire. Today, however, the mother is producing a single repetitive high note that I’ve never attributed to her before, telling her children to sit still and behave and that the man on the studio veranda with the camera is okay, even if he is a man. The bunya trees, by the way, are carrying more fruit than I’ve ever seen. One of them has forty or fifty of the large nut clusters in its top branches. Rarely has there been a season as rich as this, the trees have a vibrancy that delights the eye, the birds, insects, plants all sing of the fecundity and generosity of life from the first glimmer of dawn till dusk.

The bunya trees, by the way, are carrying more fruit than I’ve ever seen. One of them has forty or fifty of the large nut clusters in its top branches. Rarely has there been a season as rich as this, the trees have a vibrancy that delights the eye, the birds, insects, plants all sing of the fecundity and generosity of life from the first glimmer of dawn till dusk.

This fellow wasn't so happy with his reflection. He stayed there for about ten minutes, pecking at the mirror, crouching up and down, raising his wing to show the flash of yellow beneath just to make sure. This one, gender unidentified, slept in the makaranka for 36 hours before moving

This one, gender unidentified, slept in the makaranka for 36 hours before moving Clearly the weather's warming up.

Clearly the weather's warming up.

I attended a very bizarre meeting on the Coast yesterday with several members of Council.The topic was Caloundra South (yes, again, I know). For those of you who are not aware of what that is let me give the 25 word rundown: the Sunshine Coast is getting a new city of 50 000 people, on vacant land south of Caloundra. Council was doing the town planning for the development but late last year State Government said they weren’t doing it fast enough and took it over through the Urban Land Development Authority (ULDA), an outfit with even less accountability than Council.The meeting was an informal gathering of five people from Council, three Councillors and two Officers, and about fifty representatives of community groups. It had been called by Council to draw everyone’s attention to the narrow window we have been offered to even vaguely influence the development, now it’s gone to the UDLA.Certainly there is evidence of unseemly haste. Despite the recent floods casting doubts about the whole site – and the proposed report on that not being released until next year – this whole thing is supposed to be put to bed by October, brought forward from an original plan to have it begin in 2017. The problems are too many to mention, but the one major difficulty is that the development is both low-lying and adjacent to Pumicestone Passage. Those of you familiar with the district will know that the Passage runs between the mainland and Bribie Island from Caloundra in the north to Deception Bay in the south. That it is a fragile marine ecosystem already under significant stress. Building a city of that size in such a place is a disaster in the making.So what was bizarre? Sounds pretty normal for this part of the world doesn’t it?Well, the people from Council were there to help us, or at least to work with us, to draw up submissions to the ULDA (in the narrow time band available) to make sure State is apprised of the things we want for the development – like sustainability principles applied to water/sewerage/electricity, provision of the long promised public transport plan, good buffer zones, affordable housing etc.. The normal sort of stuff loony people want from government. The argument being that although State doesn’t really have much interest in this area (all the seats in this district are held by the opposition) it is an election year, and Pumicestone Passage has traction with Brisbane voters. Now that Council has no control over the development they figure that, working together with community groups, they can perhaps oblige the ULDA to still adopt the aforementioned principles of sustainability.Which is all fine and dandy except that Council, when it was in charge of the process, didn’t spend an awful lot of time listening to those of us assembled in the room, in fact ignored the vast majority of the submissions they received, many of which questioned the viability of the whole project, not so much even within the parameters that were being analysed as within the whole region. That is to say, many of the submissions were asking if it was a good idea to build another satellite city on the coast. If, indeed, this region could absorb that number of people, or, if it could, if a sprawling city of free-standing houses was the best way to go about it; if, perhaps, medium density wasn’t a better idea, or, if making the provision of a railway as a starting point was not an essential prerequisite. Amongst other things.Don’t get me wrong, it’s very probable that many of those questions appeared very naïve to a Council that had had the whole idea pressed upon them by State government in the first place. A State that was frankly unwilling to provide adequate infrastructure; but that doesn’t mean they were not valid questions and still shouldn’t be asked. The extraordinary thing from my point of view yesterday was the weird process whereby a group of people who’ve already had their painstaking work ignored by one level of government should now band with that same level of government to get their work ignored by another one.The thing is, we’ll do it. We have no choice. We’re a sad bunch, whittling away at the edifices of our institutions, trying to make them more human, trying to get them to recognise we live in an environment that includes the occasional other species. Right this minute we have a limited opportunity to perhaps influence the shape of the largest single development many of us will see in our lives. We’ll take it. But let’s not pretend it isn’t odd.

The problems are too many to mention, but the one major difficulty is that the development is both low-lying and adjacent to Pumicestone Passage. Those of you familiar with the district will know that the Passage runs between the mainland and Bribie Island from Caloundra in the north to Deception Bay in the south. That it is a fragile marine ecosystem already under significant stress. Building a city of that size in such a place is a disaster in the making.So what was bizarre? Sounds pretty normal for this part of the world doesn’t it?Well, the people from Council were there to help us, or at least to work with us, to draw up submissions to the ULDA (in the narrow time band available) to make sure State is apprised of the things we want for the development – like sustainability principles applied to water/sewerage/electricity, provision of the long promised public transport plan, good buffer zones, affordable housing etc.. The normal sort of stuff loony people want from government. The argument being that although State doesn’t really have much interest in this area (all the seats in this district are held by the opposition) it is an election year, and Pumicestone Passage has traction with Brisbane voters. Now that Council has no control over the development they figure that, working together with community groups, they can perhaps oblige the ULDA to still adopt the aforementioned principles of sustainability.Which is all fine and dandy except that Council, when it was in charge of the process, didn’t spend an awful lot of time listening to those of us assembled in the room, in fact ignored the vast majority of the submissions they received, many of which questioned the viability of the whole project, not so much even within the parameters that were being analysed as within the whole region. That is to say, many of the submissions were asking if it was a good idea to build another satellite city on the coast. If, indeed, this region could absorb that number of people, or, if it could, if a sprawling city of free-standing houses was the best way to go about it; if, perhaps, medium density wasn’t a better idea, or, if making the provision of a railway as a starting point was not an essential prerequisite. Amongst other things.Don’t get me wrong, it’s very probable that many of those questions appeared very naïve to a Council that had had the whole idea pressed upon them by State government in the first place. A State that was frankly unwilling to provide adequate infrastructure; but that doesn’t mean they were not valid questions and still shouldn’t be asked. The extraordinary thing from my point of view yesterday was the weird process whereby a group of people who’ve already had their painstaking work ignored by one level of government should now band with that same level of government to get their work ignored by another one.The thing is, we’ll do it. We have no choice. We’re a sad bunch, whittling away at the edifices of our institutions, trying to make them more human, trying to get them to recognise we live in an environment that includes the occasional other species. Right this minute we have a limited opportunity to perhaps influence the shape of the largest single development many of us will see in our lives. We’ll take it. But let’s not pretend it isn’t odd.

Ross and I spent four days walking on the Great Ocean Walk last week, starting from just south of Apollo Bay and making our way past Cape Otway Lighthouse to Johanna Beach.The walk has been billed as one of the world’s great walks so we were keen to see it, and, indeed, it does pass through beautiful country; there’s a particularly pleasant stretch along the water near Shelley Beach on the first day, then another, the next morning, which traverses some big eucalypt country on fire trails and old forestry roads. The day we did that section there was sunshine after rain and big gusts of wind making the trees throw their tops around in joy.

Ross and I spent four days walking on the Great Ocean Walk last week, starting from just south of Apollo Bay and making our way past Cape Otway Lighthouse to Johanna Beach.The walk has been billed as one of the world’s great walks so we were keen to see it, and, indeed, it does pass through beautiful country; there’s a particularly pleasant stretch along the water near Shelley Beach on the first day, then another, the next morning, which traverses some big eucalypt country on fire trails and old forestry roads. The day we did that section there was sunshine after rain and big gusts of wind making the trees throw their tops around in joy. The problem with the walk was what we found at the end of that stretch: namely, people. The walk comes out, after 10 or so kilometres, at Blanket Bay, which, you quickly discover, people can, and do, drive to. The walk-in camp is adjacent to a drive-in camp, the beach is crowded with people, family groups, tourists, school parties out practicing snorkelling. There’s litter and no privacy.The next 5kms takes you over the bluff and round to the stunning Parker Inlet, but that’s not where the camp is, the camp, which is only a drive-in camp, and thus has no water for walkers, is back up on the top of the bluff again.Not wanting to stay there we set off around the headland across the rocks, past Point Franklin, a route not recommended on the map but particularly delightful, providing us with a bit of isolation, a little sense of being alone with the world. The coast there is characterised by low cliffs and a wide stretch of exposed rocks, little sandy bays, great masses of thick ribboned kelp rising and falling with the swell. Wind and water have carved the rock into networks of lattice, exposing ancient grain, releasing subtle colours.

The problem with the walk was what we found at the end of that stretch: namely, people. The walk comes out, after 10 or so kilometres, at Blanket Bay, which, you quickly discover, people can, and do, drive to. The walk-in camp is adjacent to a drive-in camp, the beach is crowded with people, family groups, tourists, school parties out practicing snorkelling. There’s litter and no privacy.The next 5kms takes you over the bluff and round to the stunning Parker Inlet, but that’s not where the camp is, the camp, which is only a drive-in camp, and thus has no water for walkers, is back up on the top of the bluff again.Not wanting to stay there we set off around the headland across the rocks, past Point Franklin, a route not recommended on the map but particularly delightful, providing us with a bit of isolation, a little sense of being alone with the world. The coast there is characterised by low cliffs and a wide stretch of exposed rocks, little sandy bays, great masses of thick ribboned kelp rising and falling with the swell. Wind and water have carved the rock into networks of lattice, exposing ancient grain, releasing subtle colours. Ross and I were carrying more than 20kgs each, which isn’t much in the scheme of things but is a lot to have on your back nevertheless – tent, sleeping bag, mat, cooking gear, food, etc., and the reason we’re prepared to lug that sort of weight around is that it means we can get to places you can’t otherwise reach. That’s the only reason I’m prepared to do it. Time and again the GOW disappointed by dropping us, at the exact location we were supposed to camp, right where hundreds of others had just driven to. Busloads of them. As if the people who had designed the trail had simply missed the point, had failed to understand the very rationale for walking with a backpack.It’s a beautiful trail, through wonderful country, along some excellent coastline, but if you want my advice, if you want to walk it don’t carry your gear. Stay in one of the lodges. Or get your camping gear dropped off for you each day by car. Do a separate section each day with only a day-pack and your lunch. Don’t, whatever you do, expect to be alone. Don’t, like we foolishly did, expect to have a wilderness experience.

Ross and I were carrying more than 20kgs each, which isn’t much in the scheme of things but is a lot to have on your back nevertheless – tent, sleeping bag, mat, cooking gear, food, etc., and the reason we’re prepared to lug that sort of weight around is that it means we can get to places you can’t otherwise reach. That’s the only reason I’m prepared to do it. Time and again the GOW disappointed by dropping us, at the exact location we were supposed to camp, right where hundreds of others had just driven to. Busloads of them. As if the people who had designed the trail had simply missed the point, had failed to understand the very rationale for walking with a backpack.It’s a beautiful trail, through wonderful country, along some excellent coastline, but if you want my advice, if you want to walk it don’t carry your gear. Stay in one of the lodges. Or get your camping gear dropped off for you each day by car. Do a separate section each day with only a day-pack and your lunch. Don’t, whatever you do, expect to be alone. Don’t, like we foolishly did, expect to have a wilderness experience. One of the great questions about going off for a walk like that is what book to take. By definition it has to be slim, and therefore somewhat intense. Good intention doesn’t work as a guide. I’ve taken classics, Andre Gide, Dostoievski, even George Louis Borges, and found no desire to read them in wild places. This time, after almost an hour of indecision, I had a moment of wonderful inspiration and packed Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk.I’ve read a lot of Dillard and this book was my introduction to her, but I hadn’t looked at it for fifteen or twenty years. The perfect choice for the journey; lucid, sharp, funny, meaningful, observant; calling, always, the reader to attention. My good friend Ross was kind enough to let me read aloud to him (something that so rarely happens now) and so, with by the light of my little head torch we heard Living Like Weasels and Total Eclipse. In the privacy of my tent I read the title piece, about a man who kept a pebble on a shelf, protected by a square of untanned leather, only removing it for the rituals he performed several times a day: teaching it to talk.Dillard has fun with the notion, telling us the jokes people tell about him, before bringing us back to earth, reminding us that once upon a time everything spoke to us. But now ‘we have doused the burning bush and cannot rekindle it; we are lighting matches in vain under every green tree. Did the wind use to cry, and the hills shout forth praise? Now speech has vanished from among the lifeless things of earth, and living things say very little to very few.’It’s only a short essay, five pages, but it runs across cosmology, Martin Buber, lichen and the Galapagos islands. It speaks of silence. The sort of thing you want to carry in a heavy bag down amongst trees that sweep the sky with joy and waves that let rise and fall the heavy kelp.

One of the great questions about going off for a walk like that is what book to take. By definition it has to be slim, and therefore somewhat intense. Good intention doesn’t work as a guide. I’ve taken classics, Andre Gide, Dostoievski, even George Louis Borges, and found no desire to read them in wild places. This time, after almost an hour of indecision, I had a moment of wonderful inspiration and packed Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk.I’ve read a lot of Dillard and this book was my introduction to her, but I hadn’t looked at it for fifteen or twenty years. The perfect choice for the journey; lucid, sharp, funny, meaningful, observant; calling, always, the reader to attention. My good friend Ross was kind enough to let me read aloud to him (something that so rarely happens now) and so, with by the light of my little head torch we heard Living Like Weasels and Total Eclipse. In the privacy of my tent I read the title piece, about a man who kept a pebble on a shelf, protected by a square of untanned leather, only removing it for the rituals he performed several times a day: teaching it to talk.Dillard has fun with the notion, telling us the jokes people tell about him, before bringing us back to earth, reminding us that once upon a time everything spoke to us. But now ‘we have doused the burning bush and cannot rekindle it; we are lighting matches in vain under every green tree. Did the wind use to cry, and the hills shout forth praise? Now speech has vanished from among the lifeless things of earth, and living things say very little to very few.’It’s only a short essay, five pages, but it runs across cosmology, Martin Buber, lichen and the Galapagos islands. It speaks of silence. The sort of thing you want to carry in a heavy bag down amongst trees that sweep the sky with joy and waves that let rise and fall the heavy kelp. Looking towards the lighthouse from Point Franklin

Looking towards the lighthouse from Point Franklin Rockpool

Rockpool Ross and I

Ross and I

Sometimes things on which we place little or no value have terrible effects downstream. Literally, in this case. The picture shows a dead platypus on the banks of the Obi Obi, near Maleny, with the object that killed it lying alongside. We can only assume that, while nosing around on the bottom of the creek the discarded hair-tie got caught around his bill. In frustration he will have raised a claw up to push it off and suddenly found himself entangled. The rather hideous wound on his neck and left shoulder would seem to suggest that, unfortunately, death did not come quickly.

Sometimes things on which we place little or no value have terrible effects downstream. Literally, in this case. The picture shows a dead platypus on the banks of the Obi Obi, near Maleny, with the object that killed it lying alongside. We can only assume that, while nosing around on the bottom of the creek the discarded hair-tie got caught around his bill. In frustration he will have raised a claw up to push it off and suddenly found himself entangled. The rather hideous wound on his neck and left shoulder would seem to suggest that, unfortunately, death did not come quickly.

In contrast to how the proposed Cultural Plan for the Sunshine Coast Region defines culture it is interesting to note how Arts Queensland defines it in their new Sector Plan 2010-2013:'Arts and culture can be defined as all forms of creative practice and artistic and cultural expression and activity. This includes but is not limited to visual art, music, dance, writing, craft, theatre, media art, multi-arts, design, public art, events, festivals, exhibitions, community cultural development and preservation of knowledge, stories, heritage and collections.' (p8)This, while being very broad, is still much narrower than the definition which SCRC Cultural Plan is adopting. Arts Queensland focuses on ‘culture’ as Arts and Culture rather than the 'culture' of a society which is, clearly, a much less specific thing, including, as it does, business (and the many ways business is transacted, all forms of work, parenting, sport, in fact the whole kit and caboodle.)The problem arises because the word ‘culture’ has two distinct meanings which often get mixed up, in particular because, when we think of defining it, a confusion arises between the sub-categories within the meanings rather than the definitions themselves; the issues associated with high and low culture impose themselves on our ability to think about it rationally.If we can dispense with those problematic issues for a moment we see that ‘culture’ is either the thing that differentiates one society from another in the way, for example, that Sydney people are different from those who live in Guangzhou, or, for that matter, Melbourne; or, alternatively it refers to that part of society which might be summed up as the historic amassing of our artistic and philosophical achievements. We could take as examples the (possibly contentious) statement: ‘European culture up until the Twentieth century was rooted in the Christian Church, both as a director of thought and as the agency thinkers opposed over the last millenium; music, art, writing have been manifestations of our relationship to God as defined by the Church in all its different sects.’ Or, less contentiously (because it is easier to make statements about other cultures than our own) we could take the Chinese example: ‘Chinese culture arises out of a schism between three distinct world views, those of Confucius, Lao Tzu and Buddha; generally speaking art, music and writing in that country have come as a response to those beliefs, either in favour or against them.’The latter definition, it is clear, which in the dictionaries often includes the word intellectual, is about the aspirations of people, the way they define themselves both within and against the world views of society.If we’re going to develop a ‘cultural plan’ for the region and base it on the first definition then we are entering a self-defeating process; all we’re doing is producing a map of what we already think. We define ourselves as what we are and then leave it at that.By doing so we leave no room for aspiration. We abandon all those people in the society who are working to provide some sort of self-reflection and their goal of encouraging us to see ourselves more clearly. We walk away from the idea that we can become ‘more cultured.’ We also run into some serious problems with the scope of development proposed for the region. The indicative surveys that have already been done (on the basis that we’re making a plan for the generic culture of the Sunshine Coast) put ‘environment’ as the most important quality. At the same time we are planning several new towns or ‘communities’ of significant size with very little recognition of that very aspect.The example which springs to mind is the development of the greenfield site for South Caloundra, a planned city of 50 000 people. A city the size of Dubbo, (39 000) or Gladstone, (49 000). The very concept is problematic in itself, and I will be returning to this issue later, but it is made more so because we intend to simply place it into the landscape as if nothing already lives there.We’re still engaging in the terra nullius syndrome: we need to expand, there’s a bit of land with nothing on it, lets use it. Only this piece of land does happen to have several things living on it; a single example: One of the few known major colonies in Queensland of the Vulnerable Water Mouse (Xeromys myoides) is found in the area. This small endemic rodent is listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Data Book, the Federal Government’s Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) and the Queensland Nature Conservation Act. This is only one endangered species identified on the site. It is not even known if a proper study has been done to indicate if there are endangered species, either plant or animal, but it seems highly likely more are present. Moreover the development of a town the size of Dubbo in that area will undoubtedly impact on Pumicestone Passage, already recognised as a site of environmental significance. It cannot help but do so.If we’re developing a Cultural Plan based on the present society’s wish to put environmental protection as the number one priority then we’re clearly in trouble.

We also run into some serious problems with the scope of development proposed for the region. The indicative surveys that have already been done (on the basis that we’re making a plan for the generic culture of the Sunshine Coast) put ‘environment’ as the most important quality. At the same time we are planning several new towns or ‘communities’ of significant size with very little recognition of that very aspect.The example which springs to mind is the development of the greenfield site for South Caloundra, a planned city of 50 000 people. A city the size of Dubbo, (39 000) or Gladstone, (49 000). The very concept is problematic in itself, and I will be returning to this issue later, but it is made more so because we intend to simply place it into the landscape as if nothing already lives there.We’re still engaging in the terra nullius syndrome: we need to expand, there’s a bit of land with nothing on it, lets use it. Only this piece of land does happen to have several things living on it; a single example: One of the few known major colonies in Queensland of the Vulnerable Water Mouse (Xeromys myoides) is found in the area. This small endemic rodent is listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Data Book, the Federal Government’s Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) and the Queensland Nature Conservation Act. This is only one endangered species identified on the site. It is not even known if a proper study has been done to indicate if there are endangered species, either plant or animal, but it seems highly likely more are present. Moreover the development of a town the size of Dubbo in that area will undoubtedly impact on Pumicestone Passage, already recognised as a site of environmental significance. It cannot help but do so.If we’re developing a Cultural Plan based on the present society’s wish to put environmental protection as the number one priority then we’re clearly in trouble.

Discussion about development on the Sunshine Coast continues.There is a population forum and someone holds a meeting that someone else claims is nothing more than a plant for the Liberal National Party.An article in Prospect here suggests that population is not the problem, that an African villager can have ten children who each have ten children (for two generations) and all of them put together won’t emit as many greenhouse gasses as one average American in their lifetime.In the meantime I interrupt perfectly decent dinner parties to ask people what they think of the idea of five hundred thousand people living on the Coast.A man who looked like a French cineaste’s idea of an intellectual – swept back grey hair, black polo-neck shirt, slim, wearing, yes, corduroy pants – but proves to be a famous musician composer, began by saying (possibly not the best opening line but there you go):‘I am Dutch. I go back to the Netherlands from time to time to see my family. In my country when they want to make a new development they have to go through so many miles of red tape, even before they begin. But once they start thinking about it seriously the first thing they ask is where is the railway line. Where is it? How does this housing plan fit with it? Do we need to build a new one? They design the streets and the shops and the schools around where the station is. And then, if there’s money left over, last of all, they think about the road. Here! Here we are stupid. More than stupid. Here we are insane.’Curiously my own cynicism about the Dutch (you can always tell a Dutchman, but not very much) was given its comeuppance not just by this articulate gentleman but by a fascinating article in the New York Review of Books, about the cultural, social, political and artistic influence of the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century on the development of what came to be Great Britain. The article is accompanied by this marvellous picture of ‘William of Orange sets out to invade the British Isles.’ Spot the problem. I was born and raised in Scotland and we were always taught Britain hadn't been invaded since the Battle of Hastings. What’s going on here? Is there some deeply embedded racism in my system which lives in denial of the facts of history? Is this why we were taught to be suspicious of Dutchmen? Because if we listened to them we might learn the awful truth?

Spot the problem. I was born and raised in Scotland and we were always taught Britain hadn't been invaded since the Battle of Hastings. What’s going on here? Is there some deeply embedded racism in my system which lives in denial of the facts of history? Is this why we were taught to be suspicious of Dutchmen? Because if we listened to them we might learn the awful truth?

The February issue of the Australian Literary Review contains an interesting essay by Luke Slattery on the role of Macquarie and Greenway in the development of the early colony in Sydney.

‘This year,’ Slattery writes, ‘marks the bicentenary of Macquarie’s governorship and recalls his fruitful, though at times fractious, partnership with Greenway. Both men were fired by a belief in the built forms of civility and in the capacity of what we now call the public sector to provide cultural and economic stimulus … Macquarie understood instinctively that inward-dwelling civic virtues are nurtured by noble outward forms: space, mass, order, ornament … [he] embarked on a program of enlightened reform, civic improvement and territorial expansion that utterly changed the young colony’s sense of itself and its possibilities.’

How remote these sensibilities are from our present day. No matter that, as a nation, we continue to reap their benefits.I live, along with some six to ten thousand other souls, in the Hinterland behind the Sunshine Coast, a loose geographical area to the north of Brisbane, in Queensland’s south-east corner. The Sunshine Coast is not the Gold Coast, that region to the south where Mammon has entirely taken hold, it is a place still coming into being.At the moment the population is a bit more than two hundred thousand, but the plan is to ‘grow the city’ to five hundred thousand over the next ten to fifteen years. The trouble is that there is no city, there is, in fact, nothing that defines the place other than a few iconic landscape features every one of which is in danger of being destroyed by the influx of people. I speak, of course, of the beaches, the Glasshouse Mountains, the paperbark and wollum coastal swamps, and the Hinterland itself.There are several urban centres which have recently been forcibly amalgamated into one region, and the new overarching Council is trying hard to find some common thread, some defining characteristic which can unite the population and give it some sense of community. The difficulty is that all of these urban centres have seen rapid and often unstructured growth over the last two decades and there is only a vague sense of community within the smaller districts, let alone in the larger area. One might be forgiven for thinking the whole place was simply a creation of the late twentieth century’s passion for real estate.Certainly there is nothing which might be described as an architecture of the region.There are individual houses that attract attention from those interested in design, but there is barely a public building worth mention. The one place where this might have been rectified, at the new university, failed fundamentally, at the very instant of its creation, by locating itself on a greenfield site (the land was cheaper) instead of in the centre of Maroochydore where it might have given stimulus to the civic ideal. Now the institution sits, irrelevant on its windswept paddock, while around its generous fringes arises a shocking urban sprawl typified by tilt-up concrete warehouses and brick veneer homes begging to be retro-fitted the day they are complete.Anna Bligh, the Premier, had the gall to appear on the ABC’s By Design program on Radio National to spruik her government’s vision of good design. Here, on the Sunshine Coast, its absence screams from every gaudy shopping mall, from every excruciating traffic light, from the lack of a rail link to the missing hospitals.Up here in the Hinterland we take a broad view: The Sunshine Coast is buggered, might sum it up fairly neatly, we need to concentrate on what can still be saved here on the Range. But is this enough? If Macquarie and Greenway could see the possibilities in a bunch of maltreated convicts (Greenway being one himself), if they could recognise that,

‘the flowering of a civilised community could be encouraged not only by the strict regularising of the precepts of government but also by providing – in the form of buildings and roads, the planning of towns and the demarcation of counties – physical frameworks within which to develop.’

and through this recognition utterly transform the early settlement of this nation, is it not our responsibility to try to achieve the same? Even if the clay we have to work with is so much more amorphous, so given over to the lure of instant wealth?

Bernard is living in a cottage near Lake Cooroibah. It’s a little place he’s got with a small shed nearby which is perfect for his painting except that it’s so hot inside. So hot that he can only work for an hour or so before he has to retreat. It’s not as bad at night. He’s working with paint and gravity. This was how he did those remarkable paintings of cows that are a bit reminiscent of Sydney Long trees in the fawn picture, black and white pieces in which he has held up the canvas, he says, and let the paint fall this way and that, not using a brush but instead turning the backboard around, performing a sort of dance with the paint and the canvas.This new set I’m doing, he says. I’m starting with a painting of a Hills Hoist and I’ve got these skins, these cow skins hanging on it. You know that place down on the highway near Aussie World, that has the skins hanging on the fence. Like that.Bernard has an expressive forehead. There are deep horizontal parallel grooves in it that form and disappear as he talks, working as intimate contributors to his conversation. Adding nuance. We start talking about one thing and the next moment we’re onto another and then another. Hardware barns, Soirees, running away from boarding school in Ireland and Scotland. A comparison of escapes and the lessons learned.He tells the story: when he wanted out of boarding school at eleven years old he’d pretended to have a stomach ache so consistently and effectively that eventually they took his appendix out.I’ll never trust a fucking (the Irish comes out in him when he swears, fooking and shite) I’ll never trust a fucking doctor again in my life, he says.But back to Lake Cooroibah:I sometimes think I should sit down and write a best-selling novel, he says. I don’t know how else I’m going to live, that's for sure. I’ve been there for five months you know and I’m thinking that the Great Cooroibah novel probably hasn’t yet been written and maybe it’s up to me to write it. I wonder, though. I mean, if I start, will it happen?

you can see more of his work

you can see more of his work  you can see more of his work

you can see more of his work