My new novel, Hinterland, will be released on July 3, 2017, published by UQP.It is already attracting good reviews. This one, in advance of publication, is from Bookseller+Publisher: 'A small Queensland town is divided. The collapse of local industry in a once-thriving dairy community has seen farmland abandoned, repurposed for suburban sprawl or replanted by conservationists. When a government-backed plan to build a dam in the hinterland starts to gain support (and vehement opposition) from locals, tempers and old resentments start to simmer. Hinterland is Steven Lang’s third novel. It is stunning: a love story to the land and a tense exploration of the divisions arising from political alliances, personal beliefs and inherited ideals. Lang’s descriptions of the landscape are beautiful, evoking a stunning visual backdrop for the small hinterland town. His characters are vivid, revealing a true sense of their past and current allegiances, transgressions and ambitions. Glimpses of the past are cleverly interwoven with present events to create a rich narrative for each of the central players. As the novel reaches its dramatic pinnacle, where eco warriors face off against a misguided home-grown militia, it draws together themes of loss, death, rebirth and hope. Fans of Tim Winton’s Dirt Music and Lang’s previous novels, An Accidental Terrorist and 88 Lines about 44 Women, will find much to enjoy in his latest effort.' Kate Frawley is a bookseller and the manager of the Sun Bookshop. I'll be the guest at an Outspoken event on July 14 in Maleny, being interviewed by the wonderful Kate Evans from ABC Radio National's Books and Arts Daily and Books Pulse. The Outspoken website is here.

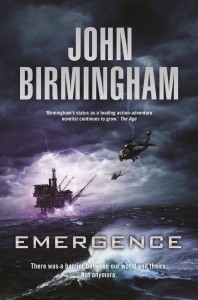

I have just finished the third instalment in John Birmingham’s Dave Hooper Trilogy: Emergence, Resistance, Ascendance. I’m reading Birmingham, of course, because I’ll be interviewing him in a couple of weeks for Outspoken. Generally we don’t want to do too many repeat authors but I’d bumped into him at the Reality Bites Festival last year in Eumundi and in response to my casual question of what he was up to he told me he was publishing not one but three (3!) books in the first half of the new year, ‘Not the sort of stuff you write, Steven, sci-fi/fantasy.’ ‘Christ,' I said, 'No orcs, I hope.’ ‘God yes, orcs,’ he replied, ‘Well, not orcs as such, but monsters from the under-realms.’ When he saw the expression on my face he launched into his speil. ‘Listen,’ he said, ‘it starts out in the Gulf of Mexico, on a rig like the Deepwater Horizon. Dave Hooper’s the security officer and he’s been on a binge, blowing his annual bonus on alcohol, sex and drugs and he’s flying back out to the rig hoping to have a few hours to sober up when they get the call there’s been an incident… monsters are boiling up from the depths. Out on the rig Dave finds himself confronted by one of these things, raging drunk on the blood of its victims, and by chance whacks it with a splitting maul, killing it and thus transferring the energy and knowledge of the beast to himself… They have, you see, drilled too deep…’Now I had a conversation with a young person the other day about this sort of thing. She said, ‘As soon as someone in a book names their sword I’m out of there.’ Which pretty much sums up my own attitude. Dave’s splitting maul, in these books, is called Lucille. Enough, you’d think, to have me running. But Birmingham brings an intelligence to this sort of guff which is both unusual and fascinating. He’s long been a weapons afficionado: it’s not uncommon to find one of his characters cradling one or other piece of hi-tech materiel, indeed on his blog Cheeseburger Gothic at one time he had a long thread asking for opinions on how to make your way across the US after civilisation had broken down, what equipment would be required… and this had given licence to a whole army of libertarians and ex-military types to spend many thousands of words listing (or arguing with each other about the relative merits of) various guns, vehicles, rocket launchers etc.. What I mean to say is that Birmingham doesn’t mind blowing things up. He doesn’t shrink from murder and mayhem, in fact he seems to to take a particular pleasure in destroying whole American cities; these are action novels in the primal sense, but they’re also scenarios to play out aspects of humanity, both social and political in unusual ways. Dave Hooper, Super Dave, is deeply flawed and being given super powers doesn’t in any way deliver him from his inner demons. Those around him, who have to try to point his new abilities in a useful direction, often refer to him as a moron, which is probably not quite fair because he’s clever enough, while lacking, perhaps, emotional intelligence. The problem being that he has to work out his issues on the world stage while fighting an ever expanding horde of monsters. (One of the more curious powers he’s gained is an extremely powerful effect on women of child-bearing status)One of the keys to writing good fiction is the ability (sometimes very difficult) to remain true to the reality you have created. What this means is no explanations given, or none outside of the course of the narrative. If there are ravenous monsters boiling up from under the ocean (and many other places besides) then that is the world the story inhabits, the author has to have complete belief in his own reality. If for a moment that wavers then the reader, too, becomes lost. Birmingham never flinches. If anything he gets better over the course of the three books – one of my complaints about some of his earlier series were that they started off remarkably, extraordinarily, well but, as the story played out, became less interesting or plausible or something – whereas in these ones the ideas and scenarios only become more fascinating and entertaining. The third book, Ascendance (which, I guess it’s some kind of spoiler, doesn’t finish the story), is a real tour de force, the first fifty thousand words are all one set piece, taking place in the space of a single night in Manhattan. Reading it I was, in the first place, unwilling to put it down, but also in a state of awe at Birmingham’s capacity to sustain the narrative in a manner that levened the mayhem with an unfolding of Dave’s understanding and his relationship to those around him, cut with wry comments on society as a whole, throwaway lines that chart the course of western civilisation in less than fifty words, or which turn the characters back on themselves and our perceptions of them. I’m not going to detail the plot or give away any more spoilers, but I will say it appears that I’ve been guilty of false advertising in my promotion of this Outspoken event by including in the blurb the statement: ‘none of this waiting a year for the sequel with our Mr Birmingham,’ because clearly there is going to be a sequel. Never mind that I can’t wait for it... I'll have to. Outspoken presents: A conversation with John Birmingham. And, introducing, Andrew McMillen, author of Talking Smack. Maleny Community Centre, July 22, 6 for 6.30pm. Tickets $18 and $12 for students, available from Maleny Bookshop 07 5494 3666 for more info visit Outspoken

I’m not going to detail the plot or give away any more spoilers, but I will say it appears that I’ve been guilty of false advertising in my promotion of this Outspoken event by including in the blurb the statement: ‘none of this waiting a year for the sequel with our Mr Birmingham,’ because clearly there is going to be a sequel. Never mind that I can’t wait for it... I'll have to. Outspoken presents: A conversation with John Birmingham. And, introducing, Andrew McMillen, author of Talking Smack. Maleny Community Centre, July 22, 6 for 6.30pm. Tickets $18 and $12 for students, available from Maleny Bookshop 07 5494 3666 for more info visit Outspoken

In the most recent issue of Rolling Stone Magazine there is a long and profoundly fascinating article by Al Gore on the climate situation entitled The Turning Point, New Hope for the Climate. It is a polemic which is full of both hope and despair, with the former, well it would be wrong to say triumphing, but at least winning out over the latter.He starts by describing the incredible advances in renewable technology, in particular solar, and what that means, how it is manifesting in different parts of the world, going on to list some of the forces ranged against its deployment. For the centre part of the piece he inevitably outlines the damage that is being done and will be done by changing weather patterns, but towards the end he takes time to point out the failure of 'democratic capitalism' to address the problem, before finally coming back to a call to action, bolstered by hope. As he says in the last paragraph, quoting Martin Luther King, 'The arc of the moral universe is long but it tilts towards justice.'This piece ties in well with another by the inimitable Bill McKibben in the New York Review of Books on the book Walden Warming: Climate Change Comes to Thoreau's Woods by Richard B Primack.It seems that Henry David Thoreau was not only the author of one 'of the greatest books any American has ever produced', he was also a formidable naturalist, spending a minimum of four hours a day walking in and around Concord, taking notes. Those painstaking observations of the timing of such natural events as the budding of flowers in spring are being used to measure the behaviour of the same plants 160 years later. The results are, generally, not good. As McKibben points out, the Sierra Club has recently ended its 120 year prohibition against engaging in illegal protest, explaining that the ongoing climate emergency required more intense engagement than they'd had so far.What these articles seem to me to suggest, and it might be that I'm just an optimist, is that, at least in other countries, some sort of tipping point has been reached in the so-called debate about Climate Change; that the effects we have already seen are dramatic enough to at last begin to exercise the minds of politicians. That Australia, with a government which is no more than the political wing of the Murdoch Press and the fossil-fuel industry, is going the other way, is a matter of deep shame and concern.

In the most recent London Review of Books there’s an article by TJ Clark on the exhibition at the Tate Modern in London of Matisse's cut-outs entitled The Urge to Strangle, the title being a reference to the making of art, Matisse having said in later life something like ‘that in order to begin painting at all he needed to feel the urge to strangle someone, or to lance an abscess in his psyche.’In the article Clark writes,‘Crowds gather at the heart of [the exhibition] drawn to an artless home movie showing the master at work. He looks, and was, unwell. Not even a rakish straw hat, part cowboy part Maurice Chevalier, can divest the scene of its pathos. There is a spot of time in the movie, after Matisse has finished his fierce fast cutting of the usual vegetable-flower-seaweed-jellyfish shapes ... when the speed suddenly slackens and the old man holds the limp paper in his hands as if reluctant to let go. He fusses with it a little, prodding and twisting the fronds in space, maybe trying to thread the shapes together, buckling them, letting them be carried for a second as they might be by a breeze or coronet. He seems to be waiting for the cut-outs to occupy space - to make space ... I thought, looking at the film sequence that I could hear the paper shapes rustle. And the word – the imagined sound – sent me back to a wonderful essay by Roland Barthes called The Rustle of Language, and especially to its last two sentences:

"I imagine myself today something like the ancient Greek as Hegel describes him: he interrogated, Hegel says, passionately, uninterruptedly, the rustle of branches, of springs, of winds, in short, the shudder of Nature, in order to perceive in it the design of an intelligence. And I – it is the shudder of meaning I interrogate, listening to the rustle of language, that language which for me, modern man, is my Nature."’

I was struck by this because it gives me a glimpse of an understanding of what people talk about when they talk about us being immersed in language, being made up of it. I know such an understanding should seem axiomatic to someone like myself, who writes, but it never really has.Interestingly enough I recently read something else which pertains to exactly this. There’s been a whole hullaballoo surrounding Karl Ove Knausgaard, the Norwegian writer of the six volume, My Struggle, which I’ve avoided dipping into for reasons that I’ve not analysed too closely – not wanting to be part of a fad as much as anything else I guess – but in the end I came across a copy of the first volume while wandering around the wonderful Foyle’s bookshop in London (on the same day as we saw the exhibition of Matisse as it happened, and, gosh, I wish I'd read the essay by TJ Clark before I saw it) and picked it up out of curiosity and found myself reading six pages right there in the store. I couldn't help but buy it. Unfortunately it became, in the end, my struggle, and I haven’t finished even this first volume. There are, however, amongst the tens of thousands of words of, quite possibly, unnecessary and irksome detail, some remarkable pieces of writing. I’m going to post one of them below. It’s five or six pages, so be warned, but I think it's worth it. And having read it maybe you can be excused reading the other 389 pages; or maybe it'll make you want to. I'm not sure it's possible to say whatever it is he's saying in less words than this, although TJ Clark hints at it. Anyway, here it is, pages 195-202 from A Death in the Family by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett."Twenty minutes later I was in my office. I hung my coat and scarf on the hook, put my shoes on the mat, made a cup of coffee, connected my computer and sat drinking coffee and looking at the title page until the screen saver kicked in and filled the screen with a myriad of bright dots.The America of the Soul. That was the title.And virtually everything in the room pointed to it, or to what it aroused in me. The reproduction of William Blake’s famous underwater-like Newton picture hanging on the wall behind me, the two framed drawings from Churchill’s eighteenth-century expedition next to it, purchased in London at some time, one of a dead whale, the other of a dissected beetle, both drawings showing several stages. A night mood by Peder Blake on the end wall, the green and the black in it. The Greenaway poster. The map of Mars I had found in an old National Geographic magazine. Beside it the two black and white photographs taken by Thomas Wagstron: one of a child’s gleaming dress, the other of a black lake beneath the surface of which you can discern the eyes of an otter. The little green metal dolphin and the little green metal helmet I had once bought on Crete and which now stood on the desk. And the books: Paracelsus, Basileios, Lucretius, Thomas Browne, Olof Rudbeck, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Seba, Werner Heisenberg, Raymond Russell and the Bible, of course, and works about national romanticism and about curiosity cabinets, Atlantis, Albrecht Durer and Max Ernst, the baroque and Gothic periods, nuclear physics and weapons of mass destruction, about forests and science in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This wasn’t about knowledge, but about the aura knowledge exuded, the places it came from, which were almost all outside the world we lived in now, yet were still within the ambivalent space where all historical objects and ideas reside.In recent years the feeling that the world was small and that I grasped everything in it had grown stronger and stronger in me, and that despite my common sense telling me that actually the reverse was true: the world was boundless and unfathomable, the number of events infinite, the present time an open door that stood flapping in the wind of history. But that is not how it felt. It felt as if the world were known, fully explored and charted, that it could no longer move in unpredicted directions, that nothing new or surprising could happen. I understood myself, I understood my surroundings, I understood society around me, and if any phenomenon should appear mysterious I knew how to deal with it.Understanding must not be confused with knowledge for I knew next to nothing – but should there be, for example, skirmishes in the borderlands of an ex-Soviet republic somewhere in Asia, whose towns I had never heard of, with inhabitants alien in everything from dress and language to everyday life and religion, and it turned out that this conflict had deep historical roots that went back to events that took place a thousand years ago, my total ignorance and lack of knowledge would not prevent me from understanding what happened, for the mind has the capacity to deal with the most alien of thoughts. This applied to everything. If I saw an insect I hadn’t come across, I knew that someone must have seen it before and categorised it. If I saw a shiny object in the sky I knew that it was either a rare meteorological phenomenon or a plane of some kind, perhaps a weather balloon, and if it was important it would be in the newspaper the following day. If I had forgotten something that happened in my childhood it was probably due to repression; if I became really furious about something it was probably due to projection, and the fact that I always tried to please people I met had something to do with my father and my relationship with him. There is no one who does not understand their own world. Someone who understands very little, a child, for example, simply moves in a more restricted world than someone who understands a lot. However, an insight into the limits of understanding has always been part of understanding: the recognition that the world outside, all those things we don’t understand not only exists but is also always greater than the world inside. From time to time I thought that what had happened, at least to me, was that the children’s world, where everything was known, and where with regard to the things that were not known, you leaned on others, those who had knowledge and ability, that this children’s world had never actually ceased to exist, it had just expanded over all these years. When I, as a nineteen year old, was confronted with the contention that the world is linguistically structured, I rejected I with what I called sound common sense, for it was obviously meaningless, the pen I held, was that supposed to be language? The window gleaming in the sun? The yard beneath me with students crossing it dressed in their autumn clothes? The lecturer’s ears, his hands? The faint smell of earth and leaves on the clothes of the woman who had just come in the door and was now sitting next to me? The sound of pneumatic drills used by the road workers who had set up their tent on the other side of St Johannes Church, the regular drone of the transformer? The rumble from the town below – was that supposed to be a linguistic rumble? My cough, is it a linguistic cough? No, that was a ridiculous idea. The world was the world, which I touched and leaned on, breathed and spat in, ate and drank, bled and vomited. It was only many years later that I began to view this differently. In a book I read about art and anatomy Nietzsche was quoted as saying that ‘physics too is an interpretation of the world and an arrangement of the world, and not an explanation on the world,’ and that ‘we have measured the value of the world with categories that refer to a purely fabricated world.’A fabricated world?Yes, the world as a superstructure, the world as a spirit, weightless and abstract, of the same material with which thoughts are woven, and through which therefore they can move unhindered. A world that after 300 years of natural science is left without mysteries. Everything is explained, everything is understood, everything lies within humanity’s horizons of comprehension, from the biggest, the universe, whose oldest observable light, the furthest boundary of the cosmos, dates from its birth fifteen billion years ago, to the smallest, the protons and neutrons and mesons of the atom. Even the phenomena that kill us we know about and understand, such as the bacteria and viruses that invade our bodies, attack our cells and cause the to grow or die. For a long time it was only nature and its laws that were made abstract and transparent in this way, but now, in our iconoclastic times, this not only applies to nature’s laws but also to its places and people. the whole of the physical world has been elevated to this sphere, everything has been incorporated into the immense imaginary realm from South American rain forests and the islands of the Pacific Ocean to the North African deserts and Eastern Europe’s tired, grey towns. Our minds are flooded with images of places we have never been, yet still know, people we have never met, yet still know and in accordance with which we, to a considerable extent, live our lives. The feeling this gives, that the world is small, tightly enclosed around itself, without opening to anywhere else, is almost incestuous, and although I knew this to be deeply untrue, since actually we know nothing about anything, still I could not escape it. The longing I always felt, which some days was so great it could hardly be controlled, had its source here. It was partly to relieve this feeling that I wrote, I wanted to open the world by writing, for myself; at the same time this is also what made me fail. The feeling that the future does not exist, that it is only more of the same, means that all utopias are meaningless. Literature has always been related to utopia, so when the utopia loses meaning, so does literature. What I was trying to do, and perhaps what all writers try to do – what on earth do I know? – was to combat fiction with fiction. What I ought to do was affirm what existed, affirm the state of things as they are, in other words, revel in the world outside instead of searching for a way out, because like this I would undoubtedly have a better life, but I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t; something had congealed inside me, a conviction was rooted inside me, and although it was essentialist, that is outmoded and furthermore romantic, I could not get past it, for the simple reason that it had not only been thought but also experienced, in these sudden states of clear-sightedness that everyone must know, where for a few seconds you catch sight of another world from the one you were in only a moment earlier, where the world seems to step forward and show itself for a brief glimpse before reverting and leaving everything as before… The last time I experienced this was on a commuter train between Stockholm and Gnesta a few months earlier. The scene outside the window was a sea of whiteness, the sky was grey and damp, we were going through an industrial area, empty railway carriages, gas tanks, factories, everything was white and grey, and the sun was setting in the west, the red rays fading into the mist, and the train in which I was travelling was not one of the rickety old run-down units that usually serviced this route, but brand new, polished and shiny, the seat was new, it smelt new, the doors in front of me opened and closed without friction, and I wasn’t thinking about anything in particular, just staring at the burning red ball in the sky and the pleasure that suffused me was so sharp and came with such intensity that it was indistinguishable from pain. What I experienced seemed to me to be of enormous significance. Enormous significance. When the moment had passed the feeling of significance did not diminish, but all of a sudden it became hard to place: exactly what was significant? And why? A train, an industrial area, sun, mist?I recognised the feeling, it was akin to the one some works of art evoke in me. Rembrandt’s picture of himself as an old man in London’s National Gallery was such a picture, Turner’s picture of the sunset over the sea off a port of antiquity at the same museum. Caravaggio’s picture of Christ in Gethsemane. Vermeer evoked the same, a few of Claude’s paintings, some of Ruisdael’s and other Dutch landscape painters, some of JC Dahl’s, almost all of Hertervig’s… But none of Rubens’ paintings, none of Manet’s, none of the English or French eighteenth century painters, with the exception of Chardin, not Whistler, or Michelangelo, and only one by Leonardo da Vinci. The experience did not favour any particular epoch, nor any particular painter, since it could apply to a single picture by a painter and leave everything else the painter did to one side. Nor did it have anything to do with what is usually termed quality; I could stand unmoved in front of fifteen pictures by Monet, and feel the warmth spread through my body in front of a Finnish impressionist of whom few outside Finland had heard.I didn’t know what it was about these pictures that made such a great impression on me. However, it was striking that they were all painted before the 1900s, within the artistic paradigm that always retained some reference to visible reality, and it was doubtless in this interlying space where it ‘happened’, where it appeared, whatever it was I saw, when the world seemed to step forward from the world. When you didn’t just see the incomprehensible in it but came very close to it. Something that didn’t speak, and that no words could reach, consequently forever out of our reach, yet within it, for not only did it surround us, we were ourselves part of it, we were ourselves of it.The fact that things other and mysterious were relevant to us had led my thoughts to angels, those mystical creatures who not only were linked to the divine but also to humanness, and therefore expressed the duality of the nature of otherness better than any other figure. At the same time there was something deeply dissatisfying about both the paintings and angels, since they both belonged to the past in such a fundamental way, the part of the past we have put behind us, that is, which no longer fitted into this world we had created where the great, the divine, the solemn, the holy, the beautiful and the true were no longer valid entities but, quite the contrary, dubious or even laughable. This meant that the great beyond, which until the Age of Enlightenment had been the divine, brought to us through the Revelation, and which in romanticism was nature, where the concept of revelation was expressed as the sublime, no longer found any expression. In art that which was beyond was synonymous with society, by which is meant the human masses, which fully encompassed its concepts and ideas of validity. As far as Norwegian art is concerned, the break came with Munch; it was in his paintings that, for the first time, man took up all the space. Whereas man was subordinate to the divine through to the Age of Enlightenment, and to the landscape he was depicted in during romanticism – the mountains are vast and intense while humans, without exception, are small – the situation is reversed with Munch. It is as if humans swallow up everything, make everything theirs. The mountains, the sea, the trees and the forests, everything is coloured by humanness. Not human actions and external life, but human feelings and inner life. And once man had taken over, there seemed not to be a way back, as indeed there was no way back for Christianity as it began to spread rapidly across Europe in the first centuries of our era. Man is gestalted by Munch, his inner life is given an outer form, the world is shaken up, and what was left after the door had been opened was the world as a gestalt: with painters after Munch it is the colours themselves, the forms themselves, not what they represent, that carry the emotion. Here we are in a world of images where the expression itself is everything, which of course means that there is no longer any dynamism between the outer and the inner, just a division. In the modernist era the division between art and world was close to absolute, or put another way, art was a world of its own. What was taken up in this world was of course a question of individual taste, and soon this taste became the very core of art, which thus could and, to a certain degree in order to survive, had to admit objects from the real world, and the situation we have arrived at now whereby the props of art no longer have any significance, all the emphasis is placed on what the art expresses, in other words, not what it is but what it thinks, what ideas it carries, such that the last remnants of objectivity, the final remnants of something outside the human world have been abandoned. Art has come to be an unmade bed, a couple of photocopiers in a room, a motorbike in an attic. And art has come to be a spectator of itself, the way it reacts, what newspapers write about it, the artist is a performer. That is how it is. Art does not know a beyond, science does not know a beyond, religion does not know a beyond, not any more. Our world is enclosed around itself, enclosed around us, and there is no way out of it. Those in this situation who call for more intellectual depth, more spirituality, have understood nothing, for the problem is that the intellect has taken over everything. Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t bodies any more, but ideas of bodies, something that is situated in our own heaven of images and conceptions within us and above us, where an increasingly large part of our lives is lived. The limits of that which cannot speak to us – the unfathomable – no longer exist. We understand everything, and we do so because we have turned everything into ourselves. Nowadays, as one might expect, all those who have occupied themselves with the neutral, the negative, the non-human in art, have turned to language, that is where the incomprehensible and the otherness have been sought, as if they were to be found on the margins of human expression, in other words, on the fringes of what we can understand, and of course actually that is logical: where else would it be found in a world that no longer acknowledges that there is a beyond?It is in this light we have to see the strangely ambiguous role death has assumed. On the one hand, it is all around us, we are inundated by news of deaths, pictures of dead people; for death, in that respect, there are no limits, it is massive, ubiquitous, inexhaustible. But this is death as an idea, death without a body, death as thought and image, death as an intellectual concept. This death is the same as the word ‘death’, the body-less entity referred to when a dead person’s name is used. For whereas, while the person is alive the name refers to the body, to where it resides, to what it does; the name becomes detached from the body when it dies and remains with the living, who, when they use the name, always mean the person he was, never the person he is now, a body which lies rotting somewhere. This aspect of death, that which belongs to the body and is concrete, physical and material, this death is hidden with such great care that it borders on a frenzy, and it works, just listen to how people who have been involuntary witnesses to fatal accidents or murders tend to express themselves. They always say the same, it was absolutely unreal, even though what they mean is the opposite. It was so real. But we no longer live in that reality. For us everything has been turned on its head, for us the real is unreal, the unreal real. And death, death is the last great beyond. That is why it has to be kept hidden. Because death might be beyond the term and beyond life, but it is not beyond the world."

I was struck by this because it gives me a glimpse of an understanding of what people talk about when they talk about us being immersed in language, being made up of it. I know such an understanding should seem axiomatic to someone like myself, who writes, but it never really has.Interestingly enough I recently read something else which pertains to exactly this. There’s been a whole hullaballoo surrounding Karl Ove Knausgaard, the Norwegian writer of the six volume, My Struggle, which I’ve avoided dipping into for reasons that I’ve not analysed too closely – not wanting to be part of a fad as much as anything else I guess – but in the end I came across a copy of the first volume while wandering around the wonderful Foyle’s bookshop in London (on the same day as we saw the exhibition of Matisse as it happened, and, gosh, I wish I'd read the essay by TJ Clark before I saw it) and picked it up out of curiosity and found myself reading six pages right there in the store. I couldn't help but buy it. Unfortunately it became, in the end, my struggle, and I haven’t finished even this first volume. There are, however, amongst the tens of thousands of words of, quite possibly, unnecessary and irksome detail, some remarkable pieces of writing. I’m going to post one of them below. It’s five or six pages, so be warned, but I think it's worth it. And having read it maybe you can be excused reading the other 389 pages; or maybe it'll make you want to. I'm not sure it's possible to say whatever it is he's saying in less words than this, although TJ Clark hints at it. Anyway, here it is, pages 195-202 from A Death in the Family by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett."Twenty minutes later I was in my office. I hung my coat and scarf on the hook, put my shoes on the mat, made a cup of coffee, connected my computer and sat drinking coffee and looking at the title page until the screen saver kicked in and filled the screen with a myriad of bright dots.The America of the Soul. That was the title.And virtually everything in the room pointed to it, or to what it aroused in me. The reproduction of William Blake’s famous underwater-like Newton picture hanging on the wall behind me, the two framed drawings from Churchill’s eighteenth-century expedition next to it, purchased in London at some time, one of a dead whale, the other of a dissected beetle, both drawings showing several stages. A night mood by Peder Blake on the end wall, the green and the black in it. The Greenaway poster. The map of Mars I had found in an old National Geographic magazine. Beside it the two black and white photographs taken by Thomas Wagstron: one of a child’s gleaming dress, the other of a black lake beneath the surface of which you can discern the eyes of an otter. The little green metal dolphin and the little green metal helmet I had once bought on Crete and which now stood on the desk. And the books: Paracelsus, Basileios, Lucretius, Thomas Browne, Olof Rudbeck, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Seba, Werner Heisenberg, Raymond Russell and the Bible, of course, and works about national romanticism and about curiosity cabinets, Atlantis, Albrecht Durer and Max Ernst, the baroque and Gothic periods, nuclear physics and weapons of mass destruction, about forests and science in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This wasn’t about knowledge, but about the aura knowledge exuded, the places it came from, which were almost all outside the world we lived in now, yet were still within the ambivalent space where all historical objects and ideas reside.In recent years the feeling that the world was small and that I grasped everything in it had grown stronger and stronger in me, and that despite my common sense telling me that actually the reverse was true: the world was boundless and unfathomable, the number of events infinite, the present time an open door that stood flapping in the wind of history. But that is not how it felt. It felt as if the world were known, fully explored and charted, that it could no longer move in unpredicted directions, that nothing new or surprising could happen. I understood myself, I understood my surroundings, I understood society around me, and if any phenomenon should appear mysterious I knew how to deal with it.Understanding must not be confused with knowledge for I knew next to nothing – but should there be, for example, skirmishes in the borderlands of an ex-Soviet republic somewhere in Asia, whose towns I had never heard of, with inhabitants alien in everything from dress and language to everyday life and religion, and it turned out that this conflict had deep historical roots that went back to events that took place a thousand years ago, my total ignorance and lack of knowledge would not prevent me from understanding what happened, for the mind has the capacity to deal with the most alien of thoughts. This applied to everything. If I saw an insect I hadn’t come across, I knew that someone must have seen it before and categorised it. If I saw a shiny object in the sky I knew that it was either a rare meteorological phenomenon or a plane of some kind, perhaps a weather balloon, and if it was important it would be in the newspaper the following day. If I had forgotten something that happened in my childhood it was probably due to repression; if I became really furious about something it was probably due to projection, and the fact that I always tried to please people I met had something to do with my father and my relationship with him. There is no one who does not understand their own world. Someone who understands very little, a child, for example, simply moves in a more restricted world than someone who understands a lot. However, an insight into the limits of understanding has always been part of understanding: the recognition that the world outside, all those things we don’t understand not only exists but is also always greater than the world inside. From time to time I thought that what had happened, at least to me, was that the children’s world, where everything was known, and where with regard to the things that were not known, you leaned on others, those who had knowledge and ability, that this children’s world had never actually ceased to exist, it had just expanded over all these years. When I, as a nineteen year old, was confronted with the contention that the world is linguistically structured, I rejected I with what I called sound common sense, for it was obviously meaningless, the pen I held, was that supposed to be language? The window gleaming in the sun? The yard beneath me with students crossing it dressed in their autumn clothes? The lecturer’s ears, his hands? The faint smell of earth and leaves on the clothes of the woman who had just come in the door and was now sitting next to me? The sound of pneumatic drills used by the road workers who had set up their tent on the other side of St Johannes Church, the regular drone of the transformer? The rumble from the town below – was that supposed to be a linguistic rumble? My cough, is it a linguistic cough? No, that was a ridiculous idea. The world was the world, which I touched and leaned on, breathed and spat in, ate and drank, bled and vomited. It was only many years later that I began to view this differently. In a book I read about art and anatomy Nietzsche was quoted as saying that ‘physics too is an interpretation of the world and an arrangement of the world, and not an explanation on the world,’ and that ‘we have measured the value of the world with categories that refer to a purely fabricated world.’A fabricated world?Yes, the world as a superstructure, the world as a spirit, weightless and abstract, of the same material with which thoughts are woven, and through which therefore they can move unhindered. A world that after 300 years of natural science is left without mysteries. Everything is explained, everything is understood, everything lies within humanity’s horizons of comprehension, from the biggest, the universe, whose oldest observable light, the furthest boundary of the cosmos, dates from its birth fifteen billion years ago, to the smallest, the protons and neutrons and mesons of the atom. Even the phenomena that kill us we know about and understand, such as the bacteria and viruses that invade our bodies, attack our cells and cause the to grow or die. For a long time it was only nature and its laws that were made abstract and transparent in this way, but now, in our iconoclastic times, this not only applies to nature’s laws but also to its places and people. the whole of the physical world has been elevated to this sphere, everything has been incorporated into the immense imaginary realm from South American rain forests and the islands of the Pacific Ocean to the North African deserts and Eastern Europe’s tired, grey towns. Our minds are flooded with images of places we have never been, yet still know, people we have never met, yet still know and in accordance with which we, to a considerable extent, live our lives. The feeling this gives, that the world is small, tightly enclosed around itself, without opening to anywhere else, is almost incestuous, and although I knew this to be deeply untrue, since actually we know nothing about anything, still I could not escape it. The longing I always felt, which some days was so great it could hardly be controlled, had its source here. It was partly to relieve this feeling that I wrote, I wanted to open the world by writing, for myself; at the same time this is also what made me fail. The feeling that the future does not exist, that it is only more of the same, means that all utopias are meaningless. Literature has always been related to utopia, so when the utopia loses meaning, so does literature. What I was trying to do, and perhaps what all writers try to do – what on earth do I know? – was to combat fiction with fiction. What I ought to do was affirm what existed, affirm the state of things as they are, in other words, revel in the world outside instead of searching for a way out, because like this I would undoubtedly have a better life, but I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t; something had congealed inside me, a conviction was rooted inside me, and although it was essentialist, that is outmoded and furthermore romantic, I could not get past it, for the simple reason that it had not only been thought but also experienced, in these sudden states of clear-sightedness that everyone must know, where for a few seconds you catch sight of another world from the one you were in only a moment earlier, where the world seems to step forward and show itself for a brief glimpse before reverting and leaving everything as before… The last time I experienced this was on a commuter train between Stockholm and Gnesta a few months earlier. The scene outside the window was a sea of whiteness, the sky was grey and damp, we were going through an industrial area, empty railway carriages, gas tanks, factories, everything was white and grey, and the sun was setting in the west, the red rays fading into the mist, and the train in which I was travelling was not one of the rickety old run-down units that usually serviced this route, but brand new, polished and shiny, the seat was new, it smelt new, the doors in front of me opened and closed without friction, and I wasn’t thinking about anything in particular, just staring at the burning red ball in the sky and the pleasure that suffused me was so sharp and came with such intensity that it was indistinguishable from pain. What I experienced seemed to me to be of enormous significance. Enormous significance. When the moment had passed the feeling of significance did not diminish, but all of a sudden it became hard to place: exactly what was significant? And why? A train, an industrial area, sun, mist?I recognised the feeling, it was akin to the one some works of art evoke in me. Rembrandt’s picture of himself as an old man in London’s National Gallery was such a picture, Turner’s picture of the sunset over the sea off a port of antiquity at the same museum. Caravaggio’s picture of Christ in Gethsemane. Vermeer evoked the same, a few of Claude’s paintings, some of Ruisdael’s and other Dutch landscape painters, some of JC Dahl’s, almost all of Hertervig’s… But none of Rubens’ paintings, none of Manet’s, none of the English or French eighteenth century painters, with the exception of Chardin, not Whistler, or Michelangelo, and only one by Leonardo da Vinci. The experience did not favour any particular epoch, nor any particular painter, since it could apply to a single picture by a painter and leave everything else the painter did to one side. Nor did it have anything to do with what is usually termed quality; I could stand unmoved in front of fifteen pictures by Monet, and feel the warmth spread through my body in front of a Finnish impressionist of whom few outside Finland had heard.I didn’t know what it was about these pictures that made such a great impression on me. However, it was striking that they were all painted before the 1900s, within the artistic paradigm that always retained some reference to visible reality, and it was doubtless in this interlying space where it ‘happened’, where it appeared, whatever it was I saw, when the world seemed to step forward from the world. When you didn’t just see the incomprehensible in it but came very close to it. Something that didn’t speak, and that no words could reach, consequently forever out of our reach, yet within it, for not only did it surround us, we were ourselves part of it, we were ourselves of it.The fact that things other and mysterious were relevant to us had led my thoughts to angels, those mystical creatures who not only were linked to the divine but also to humanness, and therefore expressed the duality of the nature of otherness better than any other figure. At the same time there was something deeply dissatisfying about both the paintings and angels, since they both belonged to the past in such a fundamental way, the part of the past we have put behind us, that is, which no longer fitted into this world we had created where the great, the divine, the solemn, the holy, the beautiful and the true were no longer valid entities but, quite the contrary, dubious or even laughable. This meant that the great beyond, which until the Age of Enlightenment had been the divine, brought to us through the Revelation, and which in romanticism was nature, where the concept of revelation was expressed as the sublime, no longer found any expression. In art that which was beyond was synonymous with society, by which is meant the human masses, which fully encompassed its concepts and ideas of validity. As far as Norwegian art is concerned, the break came with Munch; it was in his paintings that, for the first time, man took up all the space. Whereas man was subordinate to the divine through to the Age of Enlightenment, and to the landscape he was depicted in during romanticism – the mountains are vast and intense while humans, without exception, are small – the situation is reversed with Munch. It is as if humans swallow up everything, make everything theirs. The mountains, the sea, the trees and the forests, everything is coloured by humanness. Not human actions and external life, but human feelings and inner life. And once man had taken over, there seemed not to be a way back, as indeed there was no way back for Christianity as it began to spread rapidly across Europe in the first centuries of our era. Man is gestalted by Munch, his inner life is given an outer form, the world is shaken up, and what was left after the door had been opened was the world as a gestalt: with painters after Munch it is the colours themselves, the forms themselves, not what they represent, that carry the emotion. Here we are in a world of images where the expression itself is everything, which of course means that there is no longer any dynamism between the outer and the inner, just a division. In the modernist era the division between art and world was close to absolute, or put another way, art was a world of its own. What was taken up in this world was of course a question of individual taste, and soon this taste became the very core of art, which thus could and, to a certain degree in order to survive, had to admit objects from the real world, and the situation we have arrived at now whereby the props of art no longer have any significance, all the emphasis is placed on what the art expresses, in other words, not what it is but what it thinks, what ideas it carries, such that the last remnants of objectivity, the final remnants of something outside the human world have been abandoned. Art has come to be an unmade bed, a couple of photocopiers in a room, a motorbike in an attic. And art has come to be a spectator of itself, the way it reacts, what newspapers write about it, the artist is a performer. That is how it is. Art does not know a beyond, science does not know a beyond, religion does not know a beyond, not any more. Our world is enclosed around itself, enclosed around us, and there is no way out of it. Those in this situation who call for more intellectual depth, more spirituality, have understood nothing, for the problem is that the intellect has taken over everything. Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t bodies any more, but ideas of bodies, something that is situated in our own heaven of images and conceptions within us and above us, where an increasingly large part of our lives is lived. The limits of that which cannot speak to us – the unfathomable – no longer exist. We understand everything, and we do so because we have turned everything into ourselves. Nowadays, as one might expect, all those who have occupied themselves with the neutral, the negative, the non-human in art, have turned to language, that is where the incomprehensible and the otherness have been sought, as if they were to be found on the margins of human expression, in other words, on the fringes of what we can understand, and of course actually that is logical: where else would it be found in a world that no longer acknowledges that there is a beyond?It is in this light we have to see the strangely ambiguous role death has assumed. On the one hand, it is all around us, we are inundated by news of deaths, pictures of dead people; for death, in that respect, there are no limits, it is massive, ubiquitous, inexhaustible. But this is death as an idea, death without a body, death as thought and image, death as an intellectual concept. This death is the same as the word ‘death’, the body-less entity referred to when a dead person’s name is used. For whereas, while the person is alive the name refers to the body, to where it resides, to what it does; the name becomes detached from the body when it dies and remains with the living, who, when they use the name, always mean the person he was, never the person he is now, a body which lies rotting somewhere. This aspect of death, that which belongs to the body and is concrete, physical and material, this death is hidden with such great care that it borders on a frenzy, and it works, just listen to how people who have been involuntary witnesses to fatal accidents or murders tend to express themselves. They always say the same, it was absolutely unreal, even though what they mean is the opposite. It was so real. But we no longer live in that reality. For us everything has been turned on its head, for us the real is unreal, the unreal real. And death, death is the last great beyond. That is why it has to be kept hidden. Because death might be beyond the term and beyond life, but it is not beyond the world."

I’ve just finished reading Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up The Bodies, her sequel to Wolf Hall and continuation of a life of Thomas Cromwell.In the first book she took us from the fall of Cromwell’s mentor, Cardinal Wolsey – which, in theory, should also have taken Cromwell in its wake – through his ascension to the role of Master Secretary to the King. The novel was nothing short of a bravura performance, a realisation of the man from a very intimate point, as if Mantel was sitting, not in the normal close personal voice on the shoulder of the man, but actually behind his eyes, seeing what he saw at the same time as miraculously maintaining enough distance to describe him. So close, however, that she does not have room to judge him, so close that we, being in there with her, all of us readers, the world over, crowded in there in Cromwell’s head, looking out, we see the world through his lens. It is not such a bad place to be. Cromwell is an entertaining host, learned in language and art, interested in everything from brick making to the psychology of Dukes. He has a modern view of the world, the State, as well as an extraordinary history, having risen to this great height from being the son of a blacksmith.In the second book Mantel is in exactly the same place. Cromwell, however, is in an even more complex situation than when he was separating England from the Church of Rome so that Henry could escape his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. Now Henry is bored with Anne Boleyn, who he took in Katherine’s place as Queen. He has his eye on young Jane Seymour. The marriage, Henry believes, must have been false (Anne had used witchery on him) and he needs Cromwell to find him a way out of it, and Cromwell, acutely aware of how Wolsey was brought down for not achieving the King’s wishes, has to be the agent of his release.There are a thousand other concerns also in Cromwell’s mind. He has his several houses to keep and to alter, the young men he is, in turn, monitoring, the dissolution of the monasteries and the dispersal of the funds to oversee, the ill and possibly dying Katherine to keep an eye on, the relations between England and both the French and the Emperor, spies against him and for him, the jealousy and hatred of those born to privilege to deal with. Amid all this, and much more (the loss of his wife and two daughters that occurred at the end of volume one, the gathering to himself of immense wealth), he sets out to do the King’s will. He does it with coldness and clarity and not a little viciousness and what is extraordinary is that we do it with him, sitting there in his mind. Mantel, our guide, our gracious host in this place, inviting us to watch. See this: see how when the King falls from his horse while riding in the lists and everyone thinks he is dead, Cromwell, in those brief terrifying moments, lines up all the consequences of this sudden change of fortune – the different families and factions queueing up to take power, the gossamer thread upon which his own head, all his wealth and prestige, rests. See how when the King sucks back breath into his lungs and sits up the world is no longer the same. See how when, shortly after, Anne miscarries, becomes, no longer, the vessel of a possible heir, she really has to go and the way to do that is to dream up a charge of treason enacted through adultery. See how simple it is to set up, how expertly Cromwell strips away the esteem, the wealth, the illusions of those powerful men he would destroy along with her. Suddenly Cromwell’s mind, pace all that brilliance, is no longer such a pleasant place to sit within. And yet that is where we are. His mind is ours.This novel is a definition of all that literature can be, that it desires to reach, but so rarely can. It offers the possibility of knowing another man as oneself and liking it just as ill when the curtains are down and all is revealed. Here is writing that, while it might describe what seems to be another time, in truth speaks of what it is to be human. It is long, ruminative, reflective. It’s slow at the start, but it needs to be while we become accustomed to those long lists of names of the individuals involved (complicated because they have both titles and names; so that Henry Fitzroy, for example, the King’s bastard son, can be at times, Richmond, Henry or Fitzroy) but it intensifies as it progresses reaching a remarkable and sustained pitch. I did not want it to end. I wanted to begin again at the beginning as soon as I was finished. I wanted to understand how it might be possible to be King Henry VIII and to murder one’s wives and yet live on, choose another wife while blaming the last for her own fate; at the same moment as I was experiencing what it means to be Cromwell, and liking that even less.

Several articles and posts have piqued my curiosity over the last few months and what I thought to do, as part of an end of year review, is to give a brief rundown of what excited me about them and then see if there is a connecting theme or narrative. Right at the end I’ll give the links.The first was a review in the NYRB by the wonderfully named Freeman Dyson of a book by someone called David Deutsch. The book is called The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations that Transform the World, and Dyson, in his essay about it and its ideas, gave a quote from the seventeenth century British ‘prophet of modern science’ Francis Bacon to illustrate a point: ‘If we begin with certainties, we will end in doubt, but if we begin with doubts and bear them patiently, we may end in certainty.’ Bacon was talking about the use of the scientific method as a means to understand the world around us, as opposed to that which had been used for the previous few hundred centuries, which was to start from a religious perspective. It was an extremely radical viewpoint at the time but is now taken as the norm. It is, though, I believe, still a confronting and fascinating prospect, to begin in doubt and to bear it patiently.The essay, following the book, focuses on the problems we face as human beings, that we have faced and always will. Here is Dyson on Deutsch:

‘Deutsch sums up human destiny in two statements that he displays as inscriptions carved in stone, “problems are inevitable” and “problems are soluble.” … These statements apply to all aspects of human activity, to ethics and law and religion as well as to art and science. In every area, from pure mathematics and logic to war and peace, there are no final solutions and no final impossibilities. He identifies the spark of insight which gave us a clear view of our infinite future, with the beginning of the British Enlightenment in the seventeenth century. He makes a sharp distinction between the British Enlightenment and the Continental Enlightenment, which arose at the same time in France.

Both enlightenments began with the insight that problems are soluble. Both of them engaged the most brilliant minds of that age in the solution of practical problems. They diverged because many thinkers of the Continental Enlightenment believed that problems could be finally solved by utopian revolutions, while the British believed that problems were inevitable. According to Deutsch, Francis Bacon transformed the world when he took the long view foreseeing an infinite process of problem-solving guided by unpredictable successes and failures.’

Dyson goes on to reject the notion of the British as the better agents in Deutsch’s version of history as rubbish, that the Chinese and the Ancient Greeks thought similar things. I, however, was very taken by this moment of divergence between those who thought things could be solved once and for all by getting government right, and those who recognised the constant nature of the challenge… I don’t care which country or group of individuals it was, I’m simply interested to note the schism and the costs which have been associated with taking each path. The second piece comes from the evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel, with a transcript of him talking to The Edge, about Infinite Stupidity.Pagel is interested in culture. In this piece he gives a quick run down of the history of evolution from the formation of the planet until now, noting that it wasn’t until humans made the genetic change from Neanderthals to the present homo sapiens that we developed the skill of social learning:

The second piece comes from the evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel, with a transcript of him talking to The Edge, about Infinite Stupidity.Pagel is interested in culture. In this piece he gives a quick run down of the history of evolution from the formation of the planet until now, noting that it wasn’t until humans made the genetic change from Neanderthals to the present homo sapiens that we developed the skill of social learning:

‘That difference is something that anthropologists and archaeologists call social learning. It's a very difficult concept to define, but when we talk about it, all of us humans know what it means. And it seems to be the case that only humans have the capacity to learn complex new or novel behaviours, simply by watching and imitating others. And there seems to be a second component to it, which is that we seem to be able to get inside the minds of other people who are doing things in front of us, and understand why it is they're doing those things. These two things together, we call social learning.

Many people respond that, oh, of course the other animals can do social learning, because we know that the chimpanzees can imitate each other, and we see all sorts of learning in animals like dolphins and the other monkeys, and so on. But the key point about social learning is that this minor difference between us and the other species forms an unbridgeable gap between us and them. Because, whereas all of the other animals can pick up the odd behaviour by having their attention called to something, only humans seem to be able to select, among a range of alternatives, the best one, and then to build on that alternative, and to adapt it, and to improve upon it. And so, our cultures cumulatively adapt, whereas all other animals seem to do the same thing over and over and over again.

Even though other animals can learn, and they can even learn in social situations, only humans seem to be able to put these things together and do real social learning. And that has led to this ‘idea evolution.’ What is a tiny difference between us genetically has opened up an unbridgeable gap, because only humans have been able to achieve this cumulative cultural adaptation.

One way to put this in perspective is to say that you can bring a chimpanzee home to your house, and you can teach it to wash dishes, but it will just as happily wash a clean dish as a dirty dish, because it's washing dishes to be rewarded with a banana. Whereas, with humans, we understand why we're washing dishes, and we would never wash a clean one. And that seems to be the difference. It unleashes this cumulative cultural adaptation in us.’

This is just Pagel setting up the basis of an argument that has several threads: one suggesting that social learning, for all its evolutionary appeal, is not necessarily entirely good for us. That what we’ve become, over many centuries, is very good at copying and not very good at innovation. In a tribal situation, of, say, fifteen people, he points out, it would be useful to have one innovator, and in a larger group, of, say, one hundred people, it might be good to have four or five innovators. But that number would also do for a group of five hundred. He takes it further: that, in our present society, of billions, all connected to each other through the internet, we are unlikely to foster many innovators at all, because one new idea goes a long way.Another thread is a discussion of what innovation is, and why some people are better at it than others. Innovation is hard, he says, because it involves being prepared to be wrong, to be curious enough to try something in many many different ways and not be put off by not getting it right each time.Pagel, it seems to me, is linking social learning as an evolutionary force to genetic evolution, contending that the process is similar and similarly random. That those we regard as brilliant, as having genius, are those who are prepared to be curious, to put themselves in the way of random ideas and to explore them without fear of being shamed.(A slight diversion here: there is in Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift a delightful ramble, or meander, into the realm of boredom. Charlie Citrine, the narrator, is engaged in writing an exposition of the role of boredom in the development of culture and he undertakes a similar history of the planet as Pagel does, except he talks about the extraordinary, the elemental, the terminally tedious boredom of evolution, all those long millenia where nothing happens, nothing at all…)Speaking of curiosity there was a very interesting piece in Scientific American a couple of weeks ago about walking through doorways. The piece begins by reminding us of that common occurrence: we go into another room and find we cannot remember what it was we went in there to do.It seems this is not something just the more senior of us experience. It happens to everyone and it seems to be a geographical factor of passing through the doorway. Our minds are programmed to remember only what they need to. This is certainly true of our short term memory – we can recall a phone number for just long enough to read it off the page or the screen and to dial it in; a moment later it is gone because we didn’t need that information any longer. For some reason, similarly it seems, the passage through a doorway is sometimes a signal to our brain that we no longer need the information we had a moment ago,

‘some forms of memory seem to be optimized to keep information ready-to-hand until its shelf life expires, and then purge that information in favour of new stuff. Radvansky and colleagues call this sort of memory representation an “event model,” and propose that walking through a doorway is a good time to purge your event models because whatever happened in the old room is likely to become less relevant now that you have changed venues. That thing in the box? Oh, that's from what I was doing before I got here; we can forget all about that.’

The article concentrates on what has been found through experimentation and confines its speculation to that. But it occurs to me there is a link here with therapy. A lot of therapy (gestalt, voice dialogue, etc.) makes use of the conceit that the client can switch between different positions in a room to get different perspectives from within themselves on events. I remember using the analogy myself of my psyche being like a large house with many rooms (indeed, it was not until I undertook therapy that I became aware of a whole wing, a section of my house full of rooms I had no access to). The therapist couldn’t go into those rooms with me, but she could stand at the door holding it open while I entered, secure in the knowledge that I would be able to get back out, that whatever terror lurked within could not trap me. This was, as I say, an analogy or metaphor for psychological states, but I wonder if there is not some useful link here between the research on memory states and doorways, and psychological healing.I’ve mentioned in the first one of these pieces (below) that I’m reading Steven Pinker’s Our Better Angels, about the decline of violence in our time. I’ve only just started but anyone with an eye for the web or the literary pages will be aware it’s been attracting an enormous amount of attention. This idea that we are now less violent than we, as a species, used to be. Pinker spends the first half to two thirds of his big book giving hard data about how people lived and died in previous centuries, and spends the remainder of time concentrating on reasons why this might be so, suggesting, I believe, amongst other influences, the rise of reason and the growth of empathy – the possibility that we might be able to see how the wealth of our neighbour is also our wealth, that we are not all caught up in a zero sum game. As I said, I haven’t got very far into it, but the first chapter illustrates quite graphically how violence has been employed in previous eras. Not bedtime reading. It’s interesting to note that his thesis has not gone unchallenged. A review by Timothy Snyder questioned some of his assumptions.One of Pinker’s assertions is that the decline in violence is not accidental, it has come about because of identifiable factors and we would be wise to note what they are and build on them. He is, it seems to me, arguing that there are not ‘special times’ there are just different times.When I think about this I immediately think of Annie Dillard, and a passage in her book For The Time Being, which seems to articulate this in a very profound and poetic manner.The idea of special times is so hard to avoid, but there is an antidote:Under a piece entitled Now, she writes.

‘There were no formerly heroic times, there was no formerly pure generation. There is no-one here but us chickens, and so it has always been: a people busy and powerful, knowledgeable, ambivalent, important, fearful and self-aware; a people who scheme, promote, deceive, and conquer; who pray for their loved ones, and long to flee misery and death. It is a weakening and discolouring idea, that rustic people knew God personally once upon a time – or even knew selflessness or courage or literature – but that it is too late for us. In fact, the absolute is available to everyone in every age. There never was a more holy age than ours, and never a less.

There is no less holiness at this time – as you are reading this – than there was the day the Red Sea parted, or that day in the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as Ezekiel was a captive by the river Chebar, when the heavens opened and he saw visions of God. There is no whit less enlightenment under the tree by your street than there was under the Buddha’s bo tree. There is no whit less might in heaven or on earth than there was the day Jesus said “Maid, arise” to the centurion’s daughter, or the day Peter walked on water, or the night Mohammed flew to heaven on a horse. In any instant the sacred may wipe you with its finger. In any instant the bush may flare, your feet may rise, or you may see a bunch of souls in a tree. In any instant you may avail yourself of the power to love your enemies; to accept failure, slander, or the grief of loss; or to endure torture.

Purity’s time is always now. Purity is no social phenomenon, a cultural thing whose time we have missed, whose generations are dead, so we can only buy Shaker furniture. “Each and every day the Divine voice issues from Sinai,” says the Talmud. Of eternal fulfilment, Tillich said, “If it is not seen in the present, it cannot be seen at all.”’

So there’s five pieces for the year, which leaves out another three hundred and sixty, I guess, because it’s a rare day that I don’t find at least one thing of interest going on in a book, a magazine or the internet. (I’m indebted to 3Quarksdaily for consistently fascinating links) But how to make some sense of my choice?It does seem, pace Dillard as though something is happening to us as people [a shift which the old guard, clearly, resents. I am astonished by the policies being pursued, for example, by the Republican candidates for the US Presidency. Their determination to pull us back into the mire of selfishness and greed, to disband the structures we have created (the Environmental Protection Agency) that offer a skerrick of hope to a planet with, plainly, too many people. (And this attempt to plunge us back into darkness has its purveyors here in Australia, too, don’t you worry about that)]Clearly the Enlightenment is still unweaving around us. A way of thinking that occurred over two hundred years ago is only now playing out, not that this should surprise me. (As the historian who was asked what he thought the effects of the French Revolution would be, said, ‘It’s too early to tell.’) I wonder, though, if one of the reasons behind this shift I speak of, that seems inherent in all the pieces I’ve picked, is the rise of the influence of women in our culture. Not the only reason, but one of them. The society I was born into was still predominantly patriarchal, but that structure has been steadily crumbling and this does change things. It’s not that I think women are better than men, just that including their influence on the way our society organises itself might be proving significant in building understanding of ourselves as a species.It’s just a thought.Links: Review of David Deutsch’s book by Freeman Dyson: hereMark Pagel at The Edge: hereMemory and doorways, Scientific American: hereSteven Pinker can be reviewed in many different places.While I’m giving out links don’t forget to check out XKCD at hereI particularly recommend his cartoon on money here although that’s maybe not so funny as mnemonics for a new age: here please email my dad a shark

I’m going to do my best ofs in two parts, the first, this one, is about books and television, the second one, which will, in the strange world of blogs, be above this one, discusses several posts I’ve come across during the year that have fired up my mind.Best novel: A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan. No competition. It’s a novel told in, if I recall correctly, twenty-three parts, each of which functions as a short story, each one told from a different perspective, jumping forwards and backwards through time, creating, piece by piece, a world that is larger than its parts. I don’t normally like this sort of thing. The change in perspective, I find, has a tendency to rob the reader of their ability to connect with any given character, but Egan does something (I’m not sure what, but I want to find out) so that, rather than getting a fragmented collection of stories, we get an overlap that pierces to the core of both the characters’, and our own, lives. An exceeding beautiful book.A safe choice you might say, in that it won the Pulitzer, but sometimes the prize givers get it right, as they did, I believe, with Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending. I was reading some quite heavy non-fiction and came to this slim novel as a palate cleanser. What a delight it proved to be, the narrator winding us back down through the past, finding different meanings and interpretations with each turn of the staircase. It seems barely possible to have squeezed so much into so few words and yet have it feel clear and concise.Several other books deserve mention. Organising and interviewing for Outspoken I have to read a lot of books during the year in a way that I have not been accustomed to, sometimes three or four novels by one person (previously I’ve allowed books to come to me, as it were, now I have lists). I particularly enjoyed Ann Patchett’s Run. In this novel, Patchett stays with an event for a remarkable amount of time, she uses a single incident to introduce and develop a rich cast of characters, promiscuously shifting perspective between them, and yet, like Egan above, giving them all lives I found myself caring about. Patchett was, by the way, one of the most engaging speakers I’ve ever encountered, never mind having the pleasure of sharing a stage with. I also read a lot of Alex Miller and can recommend Journey to the Stone Country and Autumn Laing, his new novel. Further afield I loved Out Stealing Horses, by Per Petersen, set in the mountains on the border between Norway and Sweden, as well as Mortals, by Norman Rush. Talk about richness and density of prose and staying in a scene, milking every last drop from it. A remarkable novel indeed, set in Africa.Non-fiction: I can’t really separate out one and say it’s the best. I’ve recently read the first two volumes of Thomas Keneally’s The Australians, a very different way of relating history. I’ve heard it said that it’s a novelist’s view and this might be the case but many historians try to weave a narrative through the events they describe. Keneally spends time with individuals, not necessarily the Great Men, and through their stories hopes to illustrate the development of the nation. I found it fascinating, but the two books together, at 967 pages, are a big read and they’re heavy, too, to hold up in bed at night. A good argument for the ebook, although the hardbacks are very handsome. I was very taken by The Philosopher and the Wolf, by Mark Rowlands, and the last book from Tony Judt, that great historian of our time, Ill Fares the Land. Somewhere in there I managed Life by Keith Richards and friend, which also presents a stark picture of our time, or his time in the early years of the Rolling Stones. Beside my bed right now are two other non-fiction works, impatiently waiting for me to finish Patrick White’s The Eye of the Storm (struggling a bit here Patrick, sorry, these long diversions into punctuation-less prose make me drop off to sleep): How to Live, about the life of Montaigne, by Sarah Bakewell and The Better Angels of our Nature, by Steven Pinker, in which he discusses how and why violence has declined. I’ll drink to that.Television series also deserve a mention. The longer series give writers and directors an opportunity to develop character in a way that is novelistic, but also its own form. I watched several this year: Forbrydelsen, or The Killing, (Peter Brandt Nielsen) that dark tale from Copenhagen with the wonderful Sofie Grabol as the detective lead, although surely almost equally important was Bjarne Hendriksen as the brooding father.

Taken with the female detective lead and wanting to practice my French I also went over to look Engrenages, or Spiral, (Guy-Patrick Sainderichin and Alexandra Clert) but while loving Caroline Proust’s fiery detective I was put off by the crimes on which it focused. The French seem to love the gritty reality of violence, they relish bringing the camera in close on the dismembered bodies. Across the Atlantic there were two very different shows: Treme, Series Two, from David Simon, which I think was better than series one. One of the things I love about this drama is that it’s not interested in violence as a plot driver, the concern is music in its many and varied forms. Lastly can I recommend Community Series One and Two, (Dan Harmon). Fifty half hour sit-com shows of tremendous energy and humour starring Joel McHale and Danny Pudi. I came to these full of cynicism about American humour and found myself laughing out loud, delighting in the freshness of their approach. I particularly recommend the episodes about playing pool and the first series paintball.